What’s more, national elections in Nigeria are scheduled for next month. There is strong international concern that this violence, as bad as it is already, could spike as voters head to the polls. In fact, the upcoming elections might have been a motivating factor in Boko Haram's mayhem, as reports indicate that the BH terrorists commanded those who survived not to participate in the polls. In fact, Ian Bremmer goes even further, making an interesting point: "Boko Haram wants to force the country’s electoral commission to cancel or indefinitely postpone the vote there. We’ll likely see at least some voting there, though only under heavy security, making it easier for losers to challenge the integrity of the results."

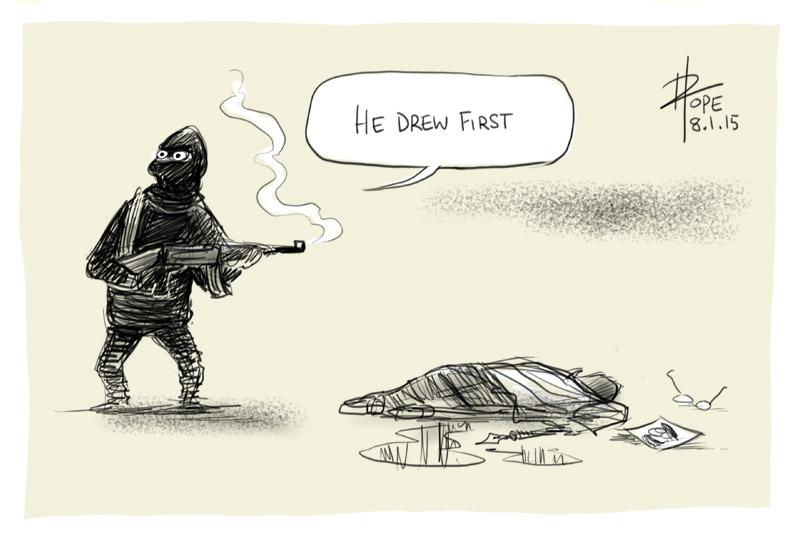

Alas, despite the large number of fatalities in Nigeria, the terror attacks there have gone largely underreported. It’s been the terror attacks in France that have dominated world news over the past week or two, pushing the Nigerian events to the back burner. Even though we now have a steady stream of 24-hour cable and satellite news outlets, as well as the Internet, media chatter and attention is still primarily driven by only issue at a time. Of course, the downside to that is that lots of other issues—at times, important issues—fly under the radar. The terror attack launched by Boko Haram is the latest example of the single-issue focus of the media. The brutality of Boko Haram has gotten barely a peep from news and policy journals, newspapers, etc., especially here in the States.

Of course, the idea of a single-issue media simply begs the

question: Why has the media privileged the attacks in France over those in Nigeria?

Why didn’t the events in Nigeria bump the coverage of France off the media’s

agenda? Or at least, why didn’t the Nigeria and French attacks receive more

equal coverage? After all, think of it this way: the Nigerian violence resulted

in roughly 100 times the death toll of all events surrounding the French

terror-counterterror violence. So what gives? What’s going on?

Well, just thinking about the US and its media, I can come

up with a few factors: 1. France is America’s friend and ally, its partner on a host of consequential issues; Nigeria isn’t.

2. Western Europe feels close to America, both

geographically and in spirit and culture. Yes, France is closer in distance,

but it’s more than that. Many within the US speak French, are knowledgeable

about French history, and routinely travel there for business and vacation. Those

things really don’t apply to Nigeria. And as a result, Nigeria feels remote and

distant.

3. There are very low expectations of Africa. Within the States, the prevailing view of Africa is that it’s unstable and war-torn and

violent. Such views don’t exist about France. So the terrorism

in Nigeria likely generates a sense of sameness, that’s its not so abnormal. With

respect to France, however, the terror attacks were framed as something

completely different: that it’s an outlier incident, something

out-of-the-ordinary, and thus more newsworthy.

Unfortunately, the relative media blackout on the Nigerian attack

hasn't been confined just to the US. Basically, it’s held across the world. To explain

this almost global media blackout, Max Abrahms, a professor at Northeastern University

and a terrorism expert, put forward several general, universal arguments in a

Tweet: (1) there aren't many experts on Boko Haram (2) Nigeria is plagued by a weak, ineffective local media (3)

the Goodluck administration has likely tried to muffle news of attacks from getting out (4) racism.

In an interview with Fusion, Abrahms fleshed out his Tweet. Boko Haram is not an official affiliate of al Qaeda, and there aren’t a lot of terrorism experts on this specific group, Abrahms said. Plus, there’s a weak media presence in that area in general, which means fewer photographers and reporters to cover the story. And the Nigerian government “has an interest in suppressing these kinds of stories.” (President Goodluck Jonathan is running for re-election next month. Voting will take place in areas controlled by Boko Haram.)

Another explanation: prejudice.

“Both the perpetrators and the victims are black, and I think if we were talking about 3,000 white people, there might be more attention, particularly in the West,” Abrahms said. The #bringbackourgirls hashtag, Abrahms speculated, connected with a wider audience likely because the victims were young girls, a particularly disturbing detail. (Boko Haram was also accused of using a 10-year-old girl to detonate a bomb at a market on Saturday, killing nearly a dozen people.)Given all of the above, it seems that an important first step that we all can take is to help get the word out regarding the atrocities in Nigeria. This blog post is my effort to do so. Greater awareness of what’s happened in Nigeria is a good thing, and just might create some momentum--both inside Nigeria and internationally--for a resolution to the violence.

If you're looking for additional information on Boko Haram and the recent

violence in Nigeria, here are some sources I encourage you to peruse: